House of Lords Committee

With no justice, there will be no peace. Enough is enough (INQUEST)

I feel hopeful. At the same time I am not complacent. As history has taught me these things have been happening time and time and time again. We are still a community, we are still a people, who needs to be healed from the traumatic events that have happened to us in the past. And this is a part of that healing.

Lee Lawrence’s mother, Cherry Groce

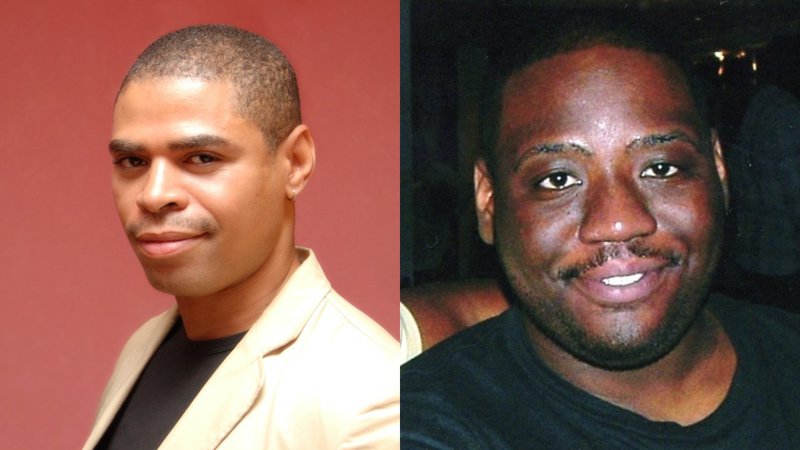

Christopher Alder, Kingsley Burrell, Darren Neville, Sheku Bayoh, Marc Cole, Cherry Groce, Jack Susianta, Adrian McDonald, Alan Marshall, Seni Lewis, Sean Rigg, Inger Shah, Joseph Scholes, Leon Patterson, Mikey Powell, Gaia Pope, Matthew Leahy and Yasser Yaqub.

These are all names of people that have died at the hands of the state since 1989. In a deeply moving video montage, brought together by film maker Ken Fero, their families talk about the pain and injustice they have faced following the death of a relative in contentious circumstances. They also talk of the strength and power in being brought together as a community to grieve, heal, and campaign for systemic change.

Whether they died in police custody or following police contact, in prison, or mental health detention or as a result of the Hillsborough football disaster, these families have since joined together as part of the campaign collective, the United Families and Friends Campaign, in their struggles for truth and accountability. INQUEST has been proud to support and work with the UFFC since its beginning,

For 22 years, the United Families and Friends Campaign, made up of some of the families above and many more, have held an annual memorial march in London in memory of their those who have died. For the first time, as a result of COVID-19 restrictions, the UFFC held the 22nd annual memorial event online.

The past year has seen unprecedented attention on the deaths of people in police custody. It has seen the murder of George Floyd in Minnesota in the United States. It has seen a renewed mass movement of hundreds of thousands of people across the world to protest for Black Lives Matter.

The anger and pain felt by many, resonated above all with many bereaved families here in the UK. In the online memorial, many families drew parallels to the systemic racialised state violence in the US, with that which led to the death of their loved ones.

George Floyd died in the hands of police, who are supposed to be our protectors. Same like my brother Sheku Bayoh. George Floyd died of asphyxia which is depriving the body of oxygen to travel to his brain and the rest of his body, same like my brother, Sheku Bayoh. George Floyd cried out, get off me I can’t breathe’, same like my brother Sheku Bayoh. For how long are we going to suffer like this? For how long? Black Lives do matter.

Kadi Johnson, sister of Sheku Bayoh

Three years since the death of her cousin, Gaia Pope, Marienna Pope-Weidemann spoke about how her family are still fighting for answers. Gaia, a survivor of rape, went missing 2017 aged 19 and was found 11 days later. They still await an inquest into her death.

We want justice for her and change for all survivors denied support by the mental health system and denied justice by the police. We want justice for Gaia, we want justice for everyone.

Marienna Pope-Weidemann, cousin of Gaia Pope

Becky Shah spoke about the 32 years she and many other families, survivors and campaigns have spent fighting for truth, justice and accountability following the Hillsborough football disaster. Becky Shah was 17 years old when her mother, Inger Shah died.

We have had many knock backs along the way from a corrupt system but we have had a few successes. Most notably in 2016 where the second inquest found that the 96 were unlawfully killed and the Liverpool fans played no part in the disaster.

Becky Shah, daughter of Inger Shah

By including footage from past annual rallies, family members who have sadly died were also remembered along the way. This includes Pauline Campbell who was a formidable campaigner for justice following the death of her daughter, Sarah in HMP Styal in 2003. She worked closely with INQUEST supporting other families and campaigning around women’s deaths in prison. In the years following Sarah’s death, Pauline would take direct action outside prison gates across the country, each time another woman died in prison. Pauline had arranged 28 such demonstrations by the time she died in 2008.

Please take the time to watch the memorial video, share it with others, participate in whatever action you can. The United Families and Friends Campaign warmly welcome other affected families to join their national campaign collective and complete this short questionnaire.

Hearing directly from families in the memorial video starkly demonstrates just how long and drawn out their struggles for justice are. The National Family Memorial Fund makes small grants available for families and their campaign groups across the UK and is an essential financial resource for families engaged in this work. Learn about how you can support the fund.

The slow pace of urgent change to prevent deaths in police custody

Last week’s report “Black people, racism and human rights” from the UK Parliament Joint Committee on Human Rights urged that: “recommendations from the Angiolini review of deaths in custody which reference institutional racism, race or discrimination must be acted upon as a matter of urgency.” What progress has been made since Angiolini herself called for urgent change three years ago?

On 30 October 2017, the landmark independent review by Dame Elish Angiolini into deaths and serious incidents in police custody in England and Wales was published. The first and only review of policing practices and the legal processes that follow police related deaths, its recommendations extend to the police service, health service and justice systems. It was seen as a blueprint for change that could save lives. Three years and one progress report later, the government seems to think its job here is done. But our work at INQUEST, a charity that works alongside families bereaved following state related deaths, tells a different story.

The starkest indicator as to the visible progress on Angiolini’s recommendations is the number of deaths of people in police custody. The most recent statistics show that the numbers remain at the same level as 10 years ago. Since the Angiolini review was published, INQUEST’s casework and monitoring indicates there has been 54 further deaths of people in police custody in England and Wales, of which 13 involved restraint. Black people are still more than twice as likely to die in police custody.

Theresa May, then Home Secretary, commissioned the review after meeting the families of Olaseni Lewis and Sean Rigg, two Black men who died following restraint by police officers whilst suffering mental ill health in 2008 and 2010. Angiolini, the former Solicitor General and Lord Advocate in Scotland, was appointed to take on the review, with INQUEST Director Deborah Coles acting as Special Advisor.

Recommendations in the review sought to address the concerns raised in these cases, such as highlighting that all restraint can cause death and the heightened dangers when someone is in mental health crisis, and the need for police to understand institutional racism and its impact. But only five months after publication, Kevin Clarke, a 35 year old Black man in a mental health crisis died after prolonged and heavy restraint by multiple police officers.

At the inquest into Kevin’s death last month the jury concluded, among a series of damning failings, that the “officers’ decision to use restraint was inappropriate because it was not based on a balanced assessment of the risks to Kevin, compared to the risks to the public and police”. The police told the inquest that they were aware of the risks of restraint, so why was there no attempt at de-escalation and why was restraint used as a first, not a last resort?

“We want mental health services better funded so the first point of response is not just reliant on the police.”

The inquest once again demonstrated the urgent need for structural and cultural change in policing, mental health and healthcare services, one which ends the reliance on police to respond to public health issues, and confronts the reality of institutional racism in our public services. Speaking after the inquest into her son’s death Kevin’s mother Wendy Clarke said: “In his memory we want to see accountability, and real change, not just in training, but the perception and response to Black people by the police and other services. We want mental health services better funded so the first point of response is not just reliant on the police.”

The current processes following deaths continue to fail bereaved families, many of whom remain unable to access anything resembling justice or accountability following a death in police custody. In response to the Angiolini review in October 2017, the then Home Secretary Amber Rudd said the government was “continuing to overhaul the police complaints and disciplinary systems, seeking to ensure that, where misconduct is found, the systems provide a transparent and robust mechanism for holding police officers to account”.

Yet following every contentious death over the past few years, the police have continued a culture of defensiveness and denial, rather than adhering to the explicit duty of candour Angiolini recommended. Time and again misconduct hearings, the disciplinary mechanism for police officers, have been dropped or dismissed following tactics by the police and their representatives to delay or avoid cooperation with the investigation.

Take the gross misconduct disciplinary process earlier this year for five Bedfordshire police officers following the restraint related death of Leon Briggs. The misconduct hearing was stopped before it had even started when Bedfordshire Police force said it would offer no evidence against the officers. Angiolini’s recommendations highlight the importance of accountability at both an individual and corporate level following restraint.

“To be told that the officers will not face any public scrutiny is further denial of justice and accountability.”

Following the decision to withdraw misconduct proceedings, Leon’s mother Margaret Briggs said: “As a family we are devastated and outraged. It is over six years since my son’s death and to be told that the officers will not face any public scrutiny is further denial of justice and accountability for Leon.”

In light of the abandoned misconduct process the focus now falls on the inquest in January 2021 to explore whether the restraint was used in an unnecessary, disproportionate or excessive way.

In the case of Sean Rigg, the misconduct panel dismissed all charges against five officers, despite an inquest jury concluding seven years previously that the level of force was unsuitable, and the restraint was unnecessary and inappropriate. This followed a series of attempts by one police officer, PC Andrew Birks, to appeal his suspension in order to retire and avoid disciplinary proceedings altogether. Such delays only add insult to the already painful and prolonged aftershock of losing a loved one in such traumatic circumstances. Angiolini had proposed a series of recommendations to remedy such delays.

“If the police acted as they were required, why is my brother dead?”

“My question remains, if the police acted as they were required, why is my brother dead? Nothing will tell me that this is justice,” said Marcia Rigg following the decision to dismiss all gross misconduct charges against the officers involved in Sean’s death.

And consider the judicial review brought by the police officer who fatally shot Jermaine Baker. The officer, known as W80, challenged the decision by the Independent Office of Police Conduct (IOPC) to direct the Metropolitan Police to bring misconduct proceedings. The officer’s challenge, which the Court of Appeal rejected, is just one example of police resistance to scrutiny after the use of lethal force. “What is important now is that W80 is held to account for his actions,” said Margaret Smith, Jermaine’s mother after the Court of Appeal handed down its judgement. “The Metropolitan Police Service have fought hard to avoid taking any action against him.”

These cases point to police impunity and a process which frustrates the prevention of abuse of power and ill treatment. They are just a few of many examples over the past few years. Others include those relating to the deaths of Olaseni Lewis, Rashan Charles, Adrian McDonald, Thomas Orchard and Duncan Tomlin. The government and state agencies clearly have much work to do before they can claim a “transparent and robust mechanism for holding police officers to account”, but where is the evidence that this work is being done?

Time and again, after deaths and a plethora of recommendations from investigations, inquests, inquiries and reviews, promises are made by the authorities responsible, that learning and action will follow. For the families, each new death exposes the lie in this promise and causes new pain. Indeed, Angiolini said one of the key themes to emerge from the review is the failure to learn lessons.

For this reason, the Angiolini review recommended the government establishes a national “Office for Article 2 Compliance”. Article 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), as enshrined in the Human Rights Act, places an obligation on the state to protect life. This Office would be accountable to Parliament, and tasked with the collation, dissemination, implementation and monitoring of learning and ensuring the consistency of its application at a national level. INQUEST has also called for the creation of this national oversight mechanism, to monitor deaths in custody and the implementation of official recommendations arising from post death investigations to ensure changes in police and practice are sustained. The government rejected Angiolini’s recommendation, and the evidence of need continues to grow.

Another injustice that unites all families bereaved following a death in police custody is the inequality of arms between themselves and state bodies from the get go. It is imperative that families secure specialist legal advice from the earliest possible stage to provide expertise on matters such as access to the body, post-mortems, communication with investigation teams and securing of evidence. Despite state bodies receiving automatic legal representation which is not subject to a merits or a means test from the taxpayer’s purse, there is no equivalent right for families. INQUEST has long campaigned for legal aid for inquests and Angiolini backed our recommendation. Yet the government rejected the overwhelming evidence in support of non means tested public funding for bereaved families.

As INQUEST Director Deborah Coles has written, families have become powerful advocates for change, turning their grief into resistance and galvanising action against injustice. They have been forced to campaign because of failing systems of investigation and accountability. Their struggles and campaigns have played a critical role in challenging the inequality, racism, discrimination and unacceptable practices of the state. For the bereaved families who invested time, emotion and energy into the Angiolini review, the failure to make progress is a betrayal.

Three years on from the Angiolini review, therefore, INQUEST is calling for the Independent Office for Police Conduct, the Home Office, NHS England and police forces to demonstrate how they have implemented the recommendations of Angiolini. There must be another progress report by the government to provide transparency on what recommendations have been “implemented” and how.

As the Black Lives Matter protests earlier this year saw hundreds of thousands of people across the world come onto the streets and stand in solidarity with George Floyd, attention was rightly drawn to the deaths of people that happen here in the UK. In October every year the United Families and Friends Campaign hold a march in London in memory of everyone who has died in state custody or care. This year on 31 October, due to COVID-19, the event took place online, with bereaved relatives of Christopher Alder, Kingsley Burrell, Darren Neville, Sheku Bayoh, Marc Cole, Cherry Groce, Jack Susianta, Adrian McDonald, Seni Lewis, Sean Rigg, Joseph Scholes, Gaia Pope, Matthew Leahy and others speaking powerfully of their loss and their experience of injustice.

In the United Friends and Family Campaign film (by Migrant Media) Kadija George, a cousin of Sheku Bayoh who died in Kirkaldy, Scotland after what police called a “forceful arrest”, said: “We don’t like welcoming families into our group, because there shouldn’t be a group like this. Nobody should be treated like this.”

Whatever actions have been taken to protect lives, it is clear that it is not enough.

We need to ask, why there is always money for the rollout of ever more powerful Tasers but youth clubs have to shut due to lack of funding? We need to think about how to create a safer and fairer and more equal society. To prevent further deaths and harm, we must look beyond policing and redirect resources into community, health, welfare and specialist services.

A damning parliamentary report on racism makes it clear: the system isn’t working (The Guardian)

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/nov/12/report-racism-human-rights-committee-findings

There is a tendency to think racism in our societies will lessen over time, and that attitudes and outcomes will inevitably improve. This belief endures despite frequent and sobering evidence of deeply entrenched racial inequalities in Britain.

One of the key points found in Black People, Racism and Human Rights, a new report from the House of Commons and House of Lords joint committee on human rights, is not only that racial progress is far from advancing, but that some things are getting worse.

Take the finding that “in the last decade, the extent to which black children and young people are disproportionately targeted by the youth justice system has increased”.

This claim is easily demonstrated by consulting youth justice statistics for 2018/2019 in England and Wales, which show that black children (who make up about 4% of the entire population aged between 10–17 years) are four times more likely to be arrested than their white counterparts, and nearly three times more likely to receive a caution or custodial sentence. Today the percentage of black children in custody has significantly increased to 28% of the entire population held in youth custody (compared with 15% a decade ago).

This is one among very many racially disproportionate outcomes that have worsened in real time despite at least eight other parliamentary publications since 2009, each of which made good recommendations for addressing racial inequalities in Britain. Add to these a litany of other inquiries in recent years, including the Windrush Lessons Learned review (2020), the race disparity audit (2017, spanning nearly all public sectors), the Lammy report (2017, looking specifically at criminal justice), the McGregor-Smith review (2017, focusing on labour markets) and the Angiolini review (2017, investigating deaths in police custody). What each of these reports makes plain is that in order to deny that racism is a key feature of disparities in these sectors, institutions and organisations must actively try to ignore it.

Perhaps this is why Baroness Lawrence asked the joint committee, “How many more lessons do we all need to learn? The lessons are there already for us to implement.” Indeed, it will soon be 30 years since the racist murder of teenager Stephen Lawrence, an event that lead, after six years of campaigning, to a public inquiry that deemed the UK’s largest police authority to be guilty of institutional racism.

Last year marked 20 years since the Macpherson report into Lawrence’s death was published and then, much as now, a key issue is the role of what is deemed “unwitting”. This is precisely how institutional racism came to be described in the inquiry into the Metropolitan Police. The report’s wide-ranging recommendations had a broad scope that translated into the 2003 Race Relations Amendment Act, and so had implications across the public sector and society more broadly.

Yet while legislating against discrimination is key, two other things matter just as much.

The first is social convention, to the extent that legislating against individual motives and objectives does not explain how racial inequalities sustain and proliferate. Take the well-established but still shocking fact, highlighted in the joint committee report, that while the rate of deaths of women in childbirth have fallen for white women (to 7 in 100,000), it has increased for black women (to 38 in 100,000). The obstetrician and gynaecologist Dr Christine Ekechi, sums up the description of possible unwitting reasons, when she says that, “People think of racism in an overt, aggressive way. But that’s not always what it is. It’s about biased assumptions – and we doctors have the same biases as anyone else.” This might include prejudiced attitudes among healthcare workers about black patients having higher pain thresholds, being too demanding, or not understanding their treatment – all of which manifests in not being listened to.

As the racial disproportionality highlighted by the Covid-19 pandemic makes plain, and as documented in the joint committee report too, though racial inequalities in health are driven by social and economic factors, harmful (and flawed) assumptions about “culture” are pervasive, and deflect responsibility on to the victims of structural discrimination.

The second issue is enforcement. It is notable that the joint committee specifically states that “the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) has been unable to adequately provide leadership and gain trust in tackling racial inequality in the protection and promotion of human rights”. It is an observation that confirms a widely held view among community groups. That an amalgamated equality body risked both diluting and de-prioritising race equality was a frequently aired concern when the EHRC was first created in 2007, by bringing all the other equality “grounds” together (race, gender, disability) before assuming responsibility for newer ones (age, sexual orientation, and religion or belief) in anticipation of the Equality Act 2010.

That these precise concerns have come to pass surprises nobody outside of an organisation that few race-equality stakeholders feel connected to, something typified by its nearly all-white board of commissioners. That it has not one black commissioner is a disgrace, and itself evidence of a profound institutional failure on race equality.

The truth is that we do not need any more reports to tell us that racial equality in Britain is in a pitiful state. What we do need is action to drive policy, implementing the myriad of good recommendations that we already have. We also need to recognise that success in race equality is going to be about more than public policy, because to tackle what is “unwitting” requires us to reflect on the character of society: asking who and what we think we are, and want to be. Achieving that task, I fear, is a long way off.

• Nasar Meer is a professor of race, identity and citizenship at the University of Edinburgh

Report into deaths in custody in England and Wales ‘kicked into long grass’

Dame Elish Angiolini says she is ‘very concerned’ that many of her recommendations have not been implemented.

The author of a high-profile report into deaths in custody says she is disappointed its demands for reform of the police, justice system and health service appear to have been “kicked into the long grass”.

Speaking three years after the launch of her report, Dame Elish Angiolini QC said key recommendations had simply not been acted upon.

The report, commissioned by Theresa May in 2015 while she was home secretary, contains 110 recommendations for improving the way police and health authorities in England and Wales deal with vulnerable people, including how the police watchdog investigates their deaths.

Among the proposed changes that have not occurred is a national oversight body that would have ensured lessons were learned from controversial deaths, and a national policing policy to limit the use of force and restraint against anyone vulnerable or with mental health problems.Advertisement

Angiolini said: “My report addressed many issues of great public concern that remain as pressing today. While I have been provided with a general update on some progress, I have not been provided with a detailed report on the progress of each recommendation, and I remain concerned that many very significant recommendations have not been progressed.

“At the launch of my report, I emphasised how important it was that its recommendations must not be kicked into the long grass,” added Angiolini, who has led a review into how prosecutors and police investigate rape cases.

According to the charity Inquest there have been at least 14 restraint-related deaths in or following police custody since Angiolini’s report was published.

Last month, an inquest jury found that the police’s inappropriate use of restraints on Kevin Clarke contributed to his death. Clarke, a 35-year-old black man, was experiencing a mental health crisis after a relapse of schizophrenia when he died following restraint in a muddy school playing field by Metropolitan Police officers in Lewisham, south London, on 9 March 2018.

During the restraint, which lasted 33 minutes, police body camera footage of the incident recorded Clarke saying: “I can’t breathe … I’m going to die,” but officers claimed they did not hear him.

The special adviser on the Angiolini review, Deborah Coles, said Clarke’s death corroborated the fact that little had changed. Coles, executive director of Inquest, also pointed out that the number of people dying in police custody remained almost the same as 10 years ago. There were 18 deaths in 2019/20, compared with 17 a decade earlier.

She said: “If the political will had existed, meaningful change would have come and avoidable deaths prevented. This is a betrayal of those who have died and their families.”

Ajibola Lewis, mother of Seni Lewis, who died following prolonged restraint on a mental health ward 10 years ago, said: “As a family who were instrumental in the setting up of the Angiolini review three years ago, we are disappointed and saddened that the majority of the recommendations have not been implemented.

“What a shame, what a missed opportunity to save lives. Nothing much has happened. The lack of accountability on the part of the state agencies speaks volumes.”

Her 23-year-old son from South Norwood, south London, died three days after he was subjected to two periods of restraint by six police officers lasting more than 30 minutes, while in hospital.

He had no history of violence or mental illness and had been taken to the hospital by his parents after an episode of mental ill health that began several days earlier.Deaths in custody: police urged to stop holding mentally ill in cellsRead more

On Saturday, families who have lost loved ones in custody – the United Families and Friends Campaign (UFFC) – held their 22nd annual memorial event, which was online for the first time this year.

Coles added: “Deaths continue to expose state violence and neglect and failings in the care of vulnerable people by the police and health services.

“The UK has a long history of black men who have died after being restrained by police. This is a systemic problem linked to structural racism and inequality and failing processes for holding the police and public authorities to account.”

Other Angiolini recommendations included making police watchdog investigators consider if discriminatory attitudes had played a part in restraint-related deaths.

The report also says the detention in police cells of those believed to have mental health issues should be phased out completely.

At the time of the report it was believed special groups had been set up in Whitehall to deal with its fallout,covering police, health and coroners.

The Home Office said: “No one should die in police custody, and we are committed to delivering meaningful change in this area. We are working with police and other agencies to ensure vulnerable people get the help they need, which has included restricting the use of police stations as places of safety, improving training for police to assess the health of detainees, and reviewing the use of current restraint methods.”

Support swells for fresh coroner’s service reform

https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/support-swells-for-fresh-coroners-service-reform-fbj6lpkr7?s=08

The parents of Susan Nicholson, who was murdered by her boyfriend in 2011, last week won a High Court battle for a fresh and full inquest into her death. Robert Trigg, who was jailed for life in 2017, had killed his previous partner, Caroline Devlin, five years before he murdered Nicholson.

Although both deaths were in similar circumstances, neither was initially deemed suspicious. The finding of accidental death in Nicholson’s case was quashed after Trigg’s conviction, but Penelope Schofield, the senior coroner in West Sussex, ruled that a new inquest would be short with no witnesses. The overturning of that decision shines a light on the role of coroners in inquests.

Remembering Seni Lewis: 10 Years On

Seni Lewis passed away on the August Bank Holiday Weekend of 2010. He was 23.

10 years after his death, we remember Seni Lewis as the adventurous, academic, athletic and caring young man that he was. We celebrate the achievements that have been made under his name thanks to the hard-work of those who loved him.

Seni’s mother, Aji Lewis, describes her son’s love of sport. “He loved basketball, football, boxing; he was quite health conscious. He had lots of friends and was very popular at school. He had a pretty face; the girls liked him.”

Aji recalls a memory of a family holiday in Florida, when Seni was a young boy. On the trip, Seni volunteered to hold a snake and went jet skiing. “Seni was an adventurer.”

“We asked him not to go out too far but he’d gone anyway. We he came back, he had a look that said he knew that he was in trouble. He asked me, ‘Mum, how far is Cuba?’ I said, ‘Cuba?’”

Seni had jet-skied out so far because he had thought that he could get to Cuba. “I suppose on a map Cuba looks near to Florida” Aji laughs as she tells the story now.

Proudly, Aji recounts how Seni always stood up for the marginalised: “he hated bullies.”

There was an occasion when Aji received a phone call from Seni’s school. It transpired that the headmaster was calling Aji to tell her how her son had defended the younger boys from the school bully. The headteacher had said: “I’ll have to have Seni come and work in my office,” and informed Aji that Seni had received handshakes on his way to the headmaster’s office after the incident.

As a young adult, Seni excelled in academia. He had studied IT at Kingston University and by the age of 23, Seni already had a degree and a masters.

Seni was aiming to go to America to study for his PhD.

Under Seni’s name immense achievements continue to be made.

In 2018, Seni’s Law was passed in the UK. Aji describes this as “a miracle.”

Seni’s Law affects mental health units, though Aji hopes that this will go further. The law mandates police officers to wear body cameras should they be called to a mental health ward.

There has to be a trainer in these units, who is responsible for the agency and contracted staff being properly skilled in de-escalation techniques.

“The idea is to get away from restraint as much as possible,” Aji explains. “and to not call the police at the slightest commotion. The police have no right to be in a mental institution.”

Anytime there is a restraint made in a unit, under Seni’s Law, a report now has to be made about the event.

The aim of the law is to make mental health units safer for patients. Aji does not want anybody to go through what she went through in losing Seni.

“Seni died, but I don’t want it to be in vain. He died and other people were saved; that’s what I would like.”

Seni’s Law received cross-party support. It received the Queen’s Assent in a matter of days. It is only the second labour MP private party bill to become law in 22 years.

What an immense achievement.

Aji Lewis now speaks to NHS staff and police officers about Seni’s death and the risks of restraint.

She proclaims: “in order for me and my family to heal, to move forward and to fight for justice, we had to forgive. I will never forget; but it is by God’s grace that I am able to forgive.”

Seni Lewis: an adventurer, an athlete, an academic and an achiever in every sense of the word. We remember him.

Mentally Yours: Seni’s Law

The Mental Health Units Use of Force Bill – also known as Seni’s Law – requires mental health inpatient units to comply with requirements around use of force policies, training and data collection. The law came into force after years of campaigning, following the death of Seni Lewis. This week Yvette chats to Seni’s mother, Aji Lewis, about why the law is needed and what it means for the future of policing and mental health inpatient services.

Parents of man who died after police restraint challenge delay over Seni’s law (The Guardian)

Aji and Conrad Lewis are urging mental health minister to ensure 2018 act takes effect

The parents of a young black man who died after being restrained in a mental health hospital are asking why a law passed in his name almost two years ago has not yet been enacted by the government.

Aji and Conrad Lewis, alongside other campaigners, have signed a letter to the mental health minister, Nadine Dorries, calling for the government to set a commencement date for the Mental Health Units (Use of Force) Act 2018.

The act, known as Seni’s law after their son, Olaseni, was introduced as a private member’s bill by the Labour MP Steve Reed. It requires mental healthcare providers to keep records of the use of force, and to train staff in de-escalation techniques to help reduce the use of restraint.

It is also intended to improve transparency and accountability, with every mental health unit having to publish its policy on the use of restraint, keep a record of occasions on which it is used, and designate one person who is responsible for implementing the policy. Police officers who attend mental health settings will have to wear body cameras.Advertisement

Olaseni, who was 23, died in 2010 soon after he was subjected to what an inquest described as “disproportionate and unreasonable” restraint at Bethlem Royal hospital in London involving 11 police officers.

His mother said at the time the law was passed: “It took us years of struggle to find out what happened to Seni: the failures at multiple levels amongst the management and staff at Bethlem Royal hospital, where, instead of looking after him, they called the police to deal with him.

“We welcome the law in his memory, in the hope that it proves to be a lasting legacy in his name, so that no other family has to suffer as we have suffered.”

The letter to Dorries, calling on her to enact the legislation urgently, has also been signed by several charity leaders, including Paul Farmer of the mental health charity Mind and Emma Thomas of YoungMinds.

Reed, who was a backbench MP when he brought in the private member’s bill and is now the shadow communities secretary, said: “The legislation I introduced to tackle dangerous restraint used disproportionately against young black men has been in place for 20 months, but it still hasn’t come into force.

“The government simply needs to set a commencement date, something that usually takes just weeks. We can’t wait any longer. Either this legislation matters to the government or it doesn’t. Ministers must bring Seni’s law into force without further delay.”

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson said: “Mental health services will continue to expand further and faster thanks to a minimum £2.3bn of extra investment a year by 2023/24 as part of the NHS long-term [plan].

“The government was fully supportive throughout the passage of the Mental Health Units (Use of Force) Act and is committed to publishing statutory guidance on the act for consultation as soon as possible.”

The Failures in the Mental Health System That Shackle Victims With Police Brutality (Justice Rapport)

Olivia Davin and Harry Robinson

“Police brutality is like a revolting chain that continues to go round and round in circles and there’s no end to it.” – Kedisha Brown-Burrell.

Seni Lewis was left lifeless after being crushed by 11 police officers. For 45 minutes, the recent masters graduate was pushed on to his stomach and restrained with two pairs of handcuffs, one arm held under his chin, the other arm twisted behind his back. His legs shackled by two leg braces. Seni was beaten three times with a baton while his brain was starved of oxygen. He was left “limp” and “braindead”; the police officers thought he was faking it. This was against police practice. The hospital staff had watched on as the life was drained from Seni’s body.

Kingsley Burrell lay braindead on life support. His face had been smothered for two hours by a blanket. His family could see taser marks all over his body as they went to switch off his life support machine. Just hours before, Kingsley had written ‘they’re going to kill me’ in a notepad that his sister, Kedisha, had given him. His forehead was covered in lumps. His lips were bulging, they had burst. The handcuffs he was wearing had been tightened to such an extent that you could see the flesh around his wrists. This was against police practice. The hospital staff had watched on as the life was drained from Kingsley’s body.

In August 2010, Seni Lewis had voluntarily admitted himself to Bethlem Royal Hospital seeking help after feeling restless and agitated. In March 2011, Kingsley Burrell had voluntarily phoned the police in Birmingham for help after he felt that there was a threat to his life whilst he was out with his son. When Seni asked if he could leave Bethlem, 11 policemen were called to restrain him. When Kingsley asked if he could leave police presence, he was detained under the Mental Health Act 1983 for “smelling of weed”.

Two men, both innocent, both full of potential, both voluntarily putting themselves in custodial positions. Both died in police custody. Neither of them had any prior history of mental health issues before these incidents.

‘Excessive, disproportionate and unreasonable restraint and force’ would be deemed the cause of both Seni and Kingsley’s deaths.

It took Kedisha Brown-Burrell, Kingsley’s sister, three years to get an inquest into Kingsley’s death. It took Aji Lewis, Seni’s mother, seven.

In 2019, PC Paul Adey was sacked for dishonesty at a misconduct hearing after it was concluded that he had previously lied about not seeing a blanket smothering Kingsley’s face. In 2017, it was concluded that the force the police used on Seni resulted in his death – however, no police officer has been prosecuted for the murder of Seni or Kingsley. In fact, there has not been a single homocide prosecution of a police officer for over 30 years.

Kedisha said: “The system just never delivers for us. We as a family and as a community don’t have any faith in justice system whatsoever.

“We’ve been traumatised for far too long. We have post-natal depression because of us hearing about what is going on in society on a daily, yearly basis. Even with George Floyd I was like: ‘no, not another fallen solider under the state’.”

The inquests showed that the police abused their power in both cases and the mental health system failed to protect these two men – like it has failed to protect countless others.

Speaking of the way the police officers defended themselves in their respective inquests, both women had this to say:

Aji: “During the inquest, it was obvious that the police were ‘coached’, because they more or less all said similar things using the same words. It was difficult to discern the truth.

“When Seni walked out of Mawdsley Hospital, before going to Bethlem, we experienced some good police practice. They deescalated the situation and Seni was relaxed. This is what police practice should be.”

Kedisha: “There was plain, blank face lying and no remorse whatsoever in the court room. No, no you weren’t doing your job. You abused your powers; that’s exactly what they did.

“We always see a chain of coverups. It was all lies. They lied non-stop. They don’t know how to tell the truth when it comes to deaths in police custody.”

INQUEST casework and monitoring reports that the proportion of BAME deaths in custody where mental-health related issues are a feature is nearly two times greater than it is in other deaths in custody.

There have been 164 deaths in police custody in the last 20 years. 8% of these deaths are black. This is disproportionately high as black people make up just 3% of the UK’s population.

Aji believes the mental health system and the police are institutionally racist. “They think all black men are Superman,” she said, talking of how the 11 police officers piled onto her son. “Incredulous”.

In 2018, Aji Lewis and her local MP Steve Reed passed the Mental Health Units Use of Force Act, widely and eponymously known as ‘Seni’s Law’.

The act increases much needed oversight and management of the use of force in mental health units. There now has to be designated trainers to submit information and statistics about their mental health unit to the Department of Health each year. The legislation also improves regulations to reduce the levels of force used whilst handling patients.

There will also be improved arrangements between the police and mental health units, including the police wearing body cameras when they come into the hospital, as a consequence of Seni’s Law. Seni’s mother says the law is important for preventing anymore grief coming from the mental health system. “We don’t want any other family to lose a loved one like we lost Seni; in appalling, appalling conditions,” she said. “There was a complete lack of accountability.”

Kedisha is working on a private prosecution case for Kingsley. She is also hoping to film a reconstructed documentation of Kingsley’s death to help educate society on police brutality and the failures of our mental health units.

The similarities between the death of Kingsley and the death of Seni are frightening – it implies an institutional problem with the UK’s mental health units, police brutality and race. These are not isolated incidents. These cases consist of the same failures in our mental health system that unjustly sends a family into disrepair.

Reflecting on the campaign for change and the need to reform a system that has failed so many, Aji eloquently quotes Nelson Mandela:

“No single person can liberate a country; you can only liberate a country if you act as a collective.”

Don’t be the spectator; the hospital staff who watched on and did nothing. Don’t shy away and stay silent about a crucial flaw in our society.

Be the collective.

For more information on the topic explore the information on the UFFC and INQUEST websites.